AI: Between Confusion & Hype

What Writers Actually Need to Know About AI (Answering Andra's Question)

This is the second piece in my Q&A mini-series with NYT bestselling author

.Andra’s Question:

Q: What are 3 specific things those of us who don’t know much about AI can do to get up to speed? Realizing I will not use AI to write for me.

First, a Primer:

Over 50% of American adults are now using AI in some form, but only a small minority are pushing it to anywhere near its full capacity, and the dominant mood is wary curiosity rather than enthusiastic embrace. Most people are touching AI at the superficial end, as a Google replacement or a recommendation engine, and some use the voice function to chat with ChatGPT. In general, there appears to be a feeling that something much bigger and more unsettling is moving under the surface. Maybe that’s the outcome of one too many Sci-Fi movies, or perhaps this one…

OK, the TV series “Black Mirror” is ahead of its time, so was Star Trek, tho. Some call it predictive programming (Interesting Engineering, Medium article, MK-Ultra “project”, etc.), and most of these have pointed toward enhanced use of computational devices in one way or another. While some are deep down Conspiracy Avenue, others were spot on. Then we add stories of Chinese surveillance and social credit scores, and the recent revelation that household US AI Labs are collaborating with DHS, and the cake to “being concerned about AI” is almost fully baked.

How many Americans are using AI?

If “using AI” includes everyday tools like recommendation feeds (Google, Bing, etc.), navigation (Apple/Google Maps), and voice assistants (Meta AI, etc.), well over 50% of U.S. adults are now regular users, bobbing between free and paid accounts. Recent polling and syntheses of multiple surveys suggest that around 55–60% of Americans report using AI at least occasionally, with about 25% saying they interact with it several times a day. When you probe specific AI-enabled products, the share jumps even higher: almost everyone uses at least one AI‑driven service in a given week, even if they do not recognize it as “AI.”

This could be AI embedded in your medical record, bank connection, or simply by using Gmail; Google’s “Gemini” is splattered all over it. Pratically, it doesn’t matter what you touch, under the hood is likely an AI working on recommending the next Netflix show, Substack article, Amazon purchase, because what we’ve come to associate with an “algorithm” is a building block AI, contributing to the overall work.

Artificial intelligence is a broad term describing computer systems performing tasks usually associated with human intelligence like decision-making, pattern recognition, or learning from experience.

Algorithms are the instructions that AI uses to carry out these tasks, therefore we could say that algorithms are the building blocks of AI, even though AI involves more advanced capabilities beyond just following instructions.

Then there’s that new “catchy word” of Generative AI: the ChatGPT, Claude, Midjourney line of products. Surveys over the last two years generally find that just over 50% of Americans have tried generative AI at least once, but the share of adults who use it as a routine tool for work, study, or personal projects is closer to the teens or low twenties.

Where did it all come from anyway? Watch this Tribeca documentary about AI.

Using AI “at full capacity” vs barely tapping it

No survey asks directly, “Are you using AI at its full capacity?” and “Do you know what full capacity of an AI actually is?”, so any estimate below has to be inferred from intensity and range of use. Perhaps, a useful way to think about it is three buckets:

Power users (maybe 5–10% of the general population): people who build workflows around AI, use multiple tools, and integrate it into research, writing, coding, analysis, or creative production on a near‑daily basis. These are the users who chain tools, automate repetitive tasks, and treat AI as an always‑on collaborator rather than a novelty. In my “day job”, I belong to this group.

Functional users (perhaps 30–40%): those who use AI regularly but narrowly—asking a chatbot to draft an email, summarize a document, brainstorm ideas, or tweak an image, without deeply rethinking how they work. They see it as handy software, not as infrastructure for a new way of doing knowledge work.

Under‑utilizers and non‑users (approximately 50% of the population): people who either do not use AI at all, or use it only indirectly through recommendation systems, smart assistants, or background features without intentional, directed use. Many in this group don’t think of themselves as AI users, even as algorithms curate their social and news feeds, drive their maps, and sort their purchase recommendations.

In that framing, fewer than 10% of true power users are anywhere close to “full capacity,” and even that is generous given how fast the AI is developing. A larger but still minority share uses AI productively but in a way that leaves the potential of AI untapped, while roughly 50% of Americans are either barely touching AI or only experiencing it passively.

How Americans feel about AI

Per The Pew Research Center, the emotional temperature around AI is best described as anxious ambivalence: people see the potential, but their default setting is concern, not excitement. Across multiple national surveys, about 50% of Americans say they are more concerned than excited about the growing use of AI in daily life, while only about 10% say they are more excited than concerned; the rest fall into a conflicted middle, feeling both at once.

Then, when Pew asked about risks and benefits, a majority of Americans rate the societal risks of AI as high, and only a minority say the benefits are similarly high. The worries cluster around a few themes: loss of human skills and connection, job disruption and downward pressure on wages, misinformation and impersonation, and a sense that the technology might be fundamentally hard to control.

At the same time, most people expect AI to matter. Large shares of the public say that AI will significantly affect their lives within a few years, and many want more personal control over how it is used rather than a simple ban or unrestricted free‑for‑all. The result is a posture that is neither full embrace nor outright rejection: AI is seen as inevitable, powerful, and somewhat opaque. It’s basically seen as a tool people are already using, often far below what it can do, while feeling uneasy about where it might take them.

Now, to Andra’s question

Q: What are 3 specific things those of us who don’t know much about AI can do to get up to speed? Realizing I will not use AI to write for me.

I’m going to give you more than three things because, well, I'd rather overdeliver. I’ll expand Andra’s question to “How do I gauge what’s happening in the writing world right now? How do I evaluate whether something is AI content (slop)? How do I know what AI can and can’t do for me?”

1. What Is AI Anyway?

The basics may bore some of you, but it’s also the stuff that most AI newsletters, Substack articles, etc., gloss right over, because they think you know it all already. Given the data points above, this may be a mistake. So, let’s start with the basics.

Large Language Models (LLMs) - the technology behind consumer-grade AI, from ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, CoPilot, to DeepSeek, etc., are machine learning prediction engines. They’re trained on massive amounts of text from books, articles, websites, images, now also films, and other material, whereas most of the materials they had no legal right to use, but…good luck complaining about that. These machines aren’t (yet) independently intelligent, but they’re expert pattern recognition devices that have learned from more text than any human can read and internalize, and then they predict what should come next based on those patterns. This isn’t confined to words; nowadays, it includes chunks of data that correlate with situations, and, through pattern matching, the responses can be trimmed down to the most applicable set of answers, and then further distilled to one “correct” response. Essentially, that’s the core mechanism: next-word or scenario prediction at massive scale.

Think of it like the autocomplete function on your phone, but trained on billions of pages of text instead of just your texting history. AI has gotten so good at predicting what comes next that it feels like a “genuine” conversation. But underneath, it’s still just a machine, using a Large Language Model, using natural resources to generate a pattern-matching and prediction-like output.

What this means:

LLMs don’t “understand” text the way humans do. They recognize patterns and predict what typically comes next in those patterns.

They don’t have knowledge or beliefs. They have statistical associations between words and phrases based on their training data.

They can’t autonomously fact-check themselves because they’re not retrieving information - they’re generating text that sounds like it fits the pattern unless you prompt them to fact-check and self-test, which is an interesting twist altogether.

There’s one caveat to this “game of prediction”: In 2017, Google’s “Deepmind” AI beat its human champion opponent in “Go”. The fascinating idea is that Go is a game in which the player relies heavily on intuition. Then again, turns out that “intuition” is a form of pattern recognition, accompanied by creativity. In 1997, Google knew that, and it kicked some Go ass in the process. *if this caught your attention, you should really watch the documentary, linked above*

Why this matters to us as writers

Once we understand that consumer LLMs are prediction engines that connect the dots in vast knowledge databases, we can better gauge what they can and can’t do for us. For instance, AI for research is used even by the great Walter Isaacson, who uses NotebookLM as an augmented research assistant. You can go as far as having ChatGPT write an article for you, but if you then forget to cut the bottom off, and go to print anyway…

2. The Machine is “Dreaming”: Understanding Hallucinations (And Why They Matter)

Imaginations and falsification aren’t limited to your ex-partner. AI is “hallucinating”, too. In technical terms, it’s when an AI system generates plausible-sounding but false information, not dissimilar to a Trump supporter, just without damaging intent.

Why hallucinations happen:

Consumer LLMs are trained to predict what text comes next, not to evaluate whether something is true. So when you ask an LLM a question, it generates text that sounds like an answer to that question, which is based on patterns it detects, while it has no “first line” mechanism to verify whether that answer is accurate. This has come to bite some attorneys in the arse, when they submitted briefs where imaginary case law was cited.

From an academic point of view, it’s like asking someone to write a research paper from memory without being allowed to check any facts. They’ll write something that sounds like a research paper, using language and structure that feels right, but the “facts” might be completely fabricated because their job is to sound plausible, not to be accurate. However, an outlier to this “accusation” is Perplexity.ai, a “real-time” research tool that provides links to the evidence it draws on for its responses.

Some of the more common types of hallucinations:

Fake citations: AI may cite books, articles, or studies that don’t exist, but sound like they should. If you get “evidence”, re-prompt the AI to add links so you can verify the citation. Yes, it’s work and it takes time. However, you may have saved that time on the front-end, and over time, the AI gets better through reinforcement corrections (learning).

Confidently wrong: It’ll state incorrect information with complete certainty.

Blended information: It’ll mix real facts with fabricated details, making it hard to separate truth from fiction.

Fake quotes: It’ll attribute statements to real people that they never said.

Mixed methods: It becomes particularly challenging when AI combines hallucinations into a single comprehensive output. To combat this, it asks for significant cognitive expenditure from the user - the exact thing you were trying to avoid by using AI in the first place.

As a reader, what you need to do:

Any specific claims (dates, numbers, names, citations) should be verified independently.

If it sounds too perfectly aligned with what you asked, be suspicious (like this response to Andra…..I’m kidding).

Check citations rigorously. If AI references a source, look it up. Often, those sources don’t exist, as in the case of the attorneys.

Cross-reference anything important with reliable sources

Listen to that “feeling in your stomach”. If it feels “off”, it may be written by AI, or at the very least, significantly augmented.

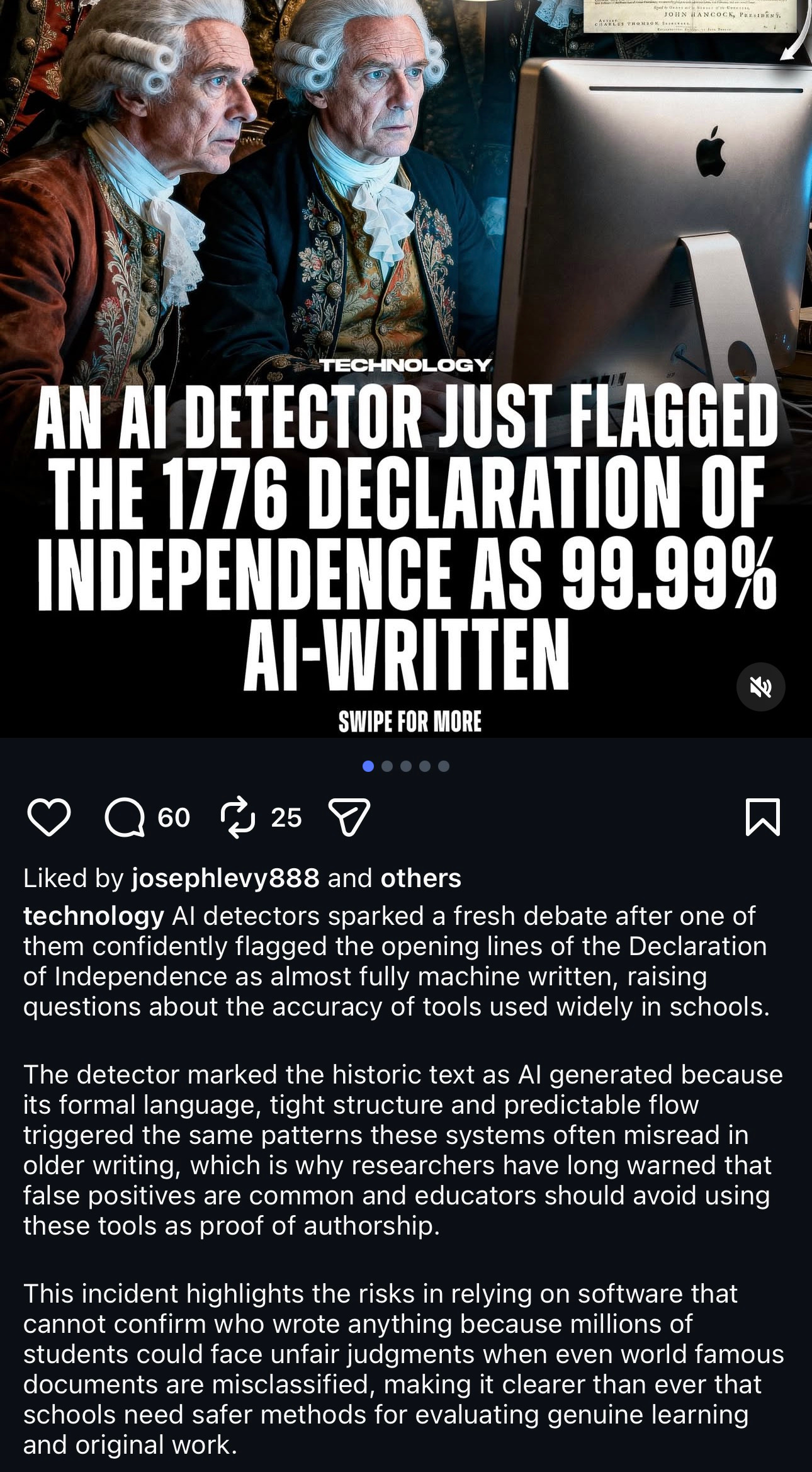

And no, you can’t rely on another AI to tell you whether something was written by an AI.

The fundamental problem:

Generally, the “garbage in, garbage out” adage applies. Unfortunately, even if you write the highest quality prompts (questions), you can’t fully prevent hallucinations. However, if you write an insufficient prompt, you’re increasing the probability of getting a questionable answer. Sure, you can reduce hallucinations, but LLMs will always be capable of generating false information because that’s how pattern recognition en masse works. It predicts plausible text, not true text. And if it “sounds true enough,” then it’s deemed to be true, unless you fact-check it.

3. What AI Can Actually Do vs What’s Hype

There are too many course sellers and AI gurus on social media, including Substack. Half, or more, of them are full of fluff but gifted marketers. So, let’s forget the marketing and look at some of the specifics of what these systems can and can’t do. And since this is Substack, we’ll look at it through the lens of writers and publishers.

What LLMs can actually do well:

Generate first drafts of generic content: This is useful for high-level marketing or copywriting, descriptions of things, or basic summaries of content. NotebookLM is particularly good at the latter, although all mainstream LLM programs can generate content that follows predictable patterns.

This is where every student rejoices, because AI can easily rewrite existing text to sound genuine. Except, a skilled instructor can slice through AI text because of its rhythm, typically overused AI words (delve?!), etc. However, one of the rubs is that AI loves to use em dashes and standard academic verbiage, which, although now associated with AI, are still the domain of writers. The same is true for “moreover” or “whereas,” which are household connectors bastardized by AI overusing them, and now the audience is conditioned to immediately accuse a writer of having used AI to write. Reverse conditioning?!

What LLMs struggle with or can’t do:

Original voice and style: They generate “generic good writing” but lack a distinctive voice. They sound like... AI. Unless…brace yourself: you train the AI on your own work! That’s when things get interesting.

Shameless plug: want to know how to do that? Ask me…

Fact verification: They can’t reliably fact-check themselves or distinguish truth from plausible-sounding fiction without being explicitly prompted to do so, and that hinges on the user having an understanding of the subject matter they’re using the AI for. In short, if you don’t know a thing about the subject, the AI will outperform you. If you’re knowledgeable, you can check the AI and make it your augmenting partner. Thus, yes, it will still take work to get it “right.”

Genuine creativity: AI recombines existing patterns. Most of the consumer-grade LLM’s don’t create new ideas or make novel connections the way human creativity does. However, due to the LLM’s ability to connect ideas, they may spur YOUR creativity, because you can offload redundant, cognitively exhausting tasks to an AI. Although DeepMind does give you a thing or two to think about…

Understanding context and nuance: Large Language Models will almost always miss subtext, they suck at irony and sarcasm is mostly not their thing, they’re culturally clumsy, and they’re never as funny as a standup comedian. However, we (at work) are about to put that to the test (AI vs Comedian).

Maintaining consistency across long-form work: The longer a piece of work you’re expecting from an AI, the more the AI will stray from its target. The longer the document, the shorter the response style. What starts with whole paragraphs ends up looking like a shitty LinkedIn post. However, there are “fixes” for that, but they take patience and a lot of personalized training data. Most users aren’t willing to spend that much time with a machine.

What this means for publishing and writing:

Unfortunately, the market is getting flooded with generic, “good enough” content, which includes more than just a few Substack writers. By any measure, this should make distinctive voices, genuine experiences, and insights more valuable, yet in a game that’s frequently overpowered by publishing frequency, quality takes time, and thereby oftentimes takes the backseat. Any social media platform, from TikTok to Instagram, Substack, and YouTube, has seen a massive increase in AI-generated content. From ElevenLabs auto-generated voice-overs to AI-produced and/or edited videos, AI-generated voice-over scripts, and the world of increasing deepfakes, these were easy to spot six months ago. Now, it’s getting more difficult. Give it 1 to 2 years, and you won’t know whether someone’s face is cloned and the voice engine has given it life.

‘s TikTok channel showcases both versions. The genuine Sabrina and the fully cloned Sabrina. She’s disclosed which character is which, but hop on over there and see if you can easily and quickly spot it. Give it another year, and what is seemingly simple to spot will seamlessly blend.And for the writers who are now concerned, you have every right to be. Some writers will continue to thrive because, for now, because they do what AI can’t: bring genuine voice, real insight, lived experience, and the kind of creativity that comes from being human in the world. Will this change? Very likely. When? I’m not sure. Until it fully changes, though, the number of successful, genuine writers will dwindle, because there’s only so much time and attention the audience has available, and AI-generated content will become the norm.

4. Spotting AI-Generated Content…

…with some semblance of reliability. The caveat is that AI is getting better. Soon, it will be good enough to blend beyond easily recognizable tells.

As a writer or a reader, the time to familiarize yourself with how to recognize AI-generated text is now. Because, as time goes by and models get better at “emulating humans”, the more effort it will take for you to catch up. And, as with any form of progress, there will be a tipping point, when you’re so far behind that catching up may not be entirely possible. And make no mistake: staying on top of it means that you have to have an interest in staying on top of it. This, once again, takes time and cognitive resources - all the things you don’t have or don’t want to expend.

These are some structural tells:

Perfect but generic organization: Clear intro, three main points, and ending with a conclusion. The structure appears to be adopted from high school essay templates. Does that make it wrong? Not at all, it just blends what we learned, and the AI has now learned, too.

Uniform paragraph length: Consistently sized paragraphs, rarely very short or very long, but frequently short bursts of “contradiction language” to further drive home a point the AI is trying to make. Then again, since LLM’s are trained on our work, they’re driving home a point the way the data suggests.

Excessive transitions: “Furthermore,” “Moreover,” “In conclusion” - formal connective tissue everywhere. Again, easy to spot, but also used for eons in academic or legal writing. Is it a surprise that the AI adopted this? Nope.

No rough edges: Everything is smooth and polished, but somehow bland. Smooth and polished is good - you want a good reading experience, no? Bland and soulless, that’s where the writer’s work comes in - it’s the author’s job to inject soul and energy, which squarely pushes us into “augmented” territory. Or, if you are a purist, you can “write from scratch”.

Language matters:

Certain phrases appear repeatedly: “It’s important to note,” “delve into,” “landscape” (as in “the publishing landscape”), “multifaceted,” “nuanced.” The issue is that AI is overusing words that it learned from us. Does that make it wrong? No, it just makes it a prediction engine that does what seems “correct”, only to overuse on “correctness”.

Hedging language: “May,” “might,” “could potentially” - because the AI is sneaky and averse to definitive statements, thereby leaving room for corrections. After all, it’s predicting probable text. Pending your prompt, this can be changed, though.

Lists and bullet points: Unless you specifically tell an AI to use a specific blend between narrative and listicles, AI is a tool for efficiency, and it loves nothing more than organizing information into lists.

The gut check:

Does what you read feel like a human wrote it, or does it feel like a very competent student who studied the topic for an hour and then wrote an essay? Informed but, perhaps, a bit soulless. AI writing often has that “trying hard to sound smart” quality, lacking genuine authority or voice. Then again, so do I…so…crap.

Thus, the caveat:

Some humans write like AI, and AI is getting better at adopting human writing patterns. For now, there are still somewhat reliable indicators, especially when you see multiple issues in the same article.

The bigger question is whether it matters? Is the authenticity of a writer who carefully curates, verifies, and cross-checks the output of an AI in question? Or is augmented content creation a sign of understanding that a car, which you have to drive on public roads responsibly, gets you to the destination quicker than a horse buggy?

5. What’s a High-Quality Prompt Anyway? (Garbage In, Garbage Out)

Even if you never use AI to write or build your grocery list, understanding prompts helps you understand how the LLMs work and what they can or can’t do.

The fundamental principle: You get what you ask for. As any attorney will tell you, if you ask bad questions, you’ll get bad answers.

Thus, if you give them vague or poorly constructed prompts, they’ll predict vague and poorly reasoned responses. If you give them specific, well-structured prompts, they’ll generate more useful outcomes.

It dawned on me that I should ask AI, since it’s the king of the castle on this subject:

“What makes a prompt high-quality:” The AI responses are in italics. My additions in regular font.

Specificity over vagueness:

Bad: “Write about climate change.”

Better: “Write a 500-word op-ed arguing that coastal cities should invest in flood infrastructure now rather than waiting for disaster, using examples from New Orleans and Miami”

Now, there’s a “best,” of course: prompt the AI to take on the role of an expert, reference case studies, build a knowledge base to draw from, and give it guardrails to adhere to.

Context and constraints:

Bad: “Write a blog post about marketing.”

Better: “Write a blog post for small business owners who have no marketing background, explaining three basic marketing principles they can implement this week with zero budget. Use conversational tone and include specific examples.”

Best: Instruct the AI to write from a specific position, to solve a specific problem. The more granular the instructions and the problem description, the better the output. If you want a post about marketing, prompt it to write from the position of a marketer, reference names, styles, etc., to establish context - and make sure that you’re at least somewhat familiar with what you’re asking it to do.

Clear role and audience:

Bad: “Explain quantum physics”

Better: “Explain quantum superposition to a curious 12-year-old who loves science but has no physics background. Use analogies and avoid jargon.”

Best: You can see where this is going. Instructions matter. As humans, we’re mostly conditioned to giving answers. With AI, this changes: we need to learn to ask better questions.

Format and structure guidance:

Bad: “Give me information about the Civil War”

Better: “Create a timeline of the five most significant battles of the Civil War, with 2-3 sentences per battle explaining why it was strategically important”

Best:….. (you can create your own mental model to answer what’s missing).

So, we have to change our approach

Since we understood our parents’ requests, we’ve been conditioned to provide answers. Then we go to school, and it’s all about answers and, worse yet, regurgitation, frequently without checking for understanding.

AI turns this upside down. LLMs provide answers, which, considering what they’re trained on, makes perfect sense. Rarely have humans published anything that consists of more questions, but we only get onto the shelves, digital or library, if we provide answers.

This pushes us into a different cognitive territory. Rather than rambling answers, which the AI does every bit as well as we do, we have to re-train ourselves to think clearly about what we actually want and then ask with clarity and precision. This is commonly the domain of journalists, philosophers, psychologists, and other soft-skilled people. Which also gets to say that skills that used to be belittled are now seeing a massive resurgence in usefulness.

6. The Challenge: Try It Yourself

If you haven’t yet, I’d like to invite you to actually engage with Large Language Models.

Try this: Go to ChatGPT (free version) or Claude (free version).

Then, use these three prompts and evaluate the results:

Prompt 1 (Vague): “Write about the future of publishing”

See what you get. It’ll probably be generic, surface-level, and bland. This shows you what happens with vague prompts.

Prompt 2 (Specific): “Write a 300-word essay arguing that traditional publishers will survive the AI content flood, specifically because they can verify author authenticity and editorial quality. Include one specific example of why this matters to readers. Write in a conversational but authoritative tone.”

See how the output improves with specificity. Notice what’s better, and what’s still generic.

Then, build Prompt 3: From a specific position of authority, upload reference documents that you’re familiar with (to reduce hallucinations), provide guardrails, determine the desired output (narrative vs summary vs bullet points), and if you’re really cheeky, ask the LLM to end with a paragraph on “how did you generate this response. What patterns in your training data, beyond what I supplied, did you use? What are the limitations of your response?”

What This All Means for Writers

I stuck the entire article (above) into AI, and asked it to summarize. You can tell me whether it’s sufficient or FoS (full of 💩).

Here’s my synthesis for Andra and anyone else trying to understand AI without using it to write:

What you need to know:

LLMs are prediction engines, not knowledge databases or creative minds

They hallucinate regularly - this is fundamental to how they work

They can generate generic content well but struggle with voice, insight, and originality

You can learn to spot AI-generated content by recognizing the patterns

Understanding prompts helps you understand how the technology works

Direct experience demystifies the technology

What this means for your writing:

The market’s getting flooded with generic content. This makes your distinctive voice, genuine insight, and lived experience more valuable than ever. The things AI can’t do - original thinking, real voice, human connection - are exactly what readers will pay for.

Don’t compete with AI on generic content. Double down on what makes you irreplaceable: your unique perspective, your specific knowledge, your authentic voice.

What to do next:

Spend 30 minutes doing the challenge above to demystify the technology

Start noticing AI-generated content in the wild (you’ll spot it everywhere once you know the tells)

Focus your own writing on what AI can’t replicate: genuine insight, distinctive voice, lived experience

You don’t need to use AI to thrive as a writer in an AI world. You need to understand what it is, what it can do, and what it can’t do. Then you write from the place where you’re irreplaceable.

Was that good enough?

Coming full circle

Andra asked how to get up to speed on AI without using it to write. My take is that you can’t avoid AI anymore. It’s in your research tools, your editing software, the readers’ newsfeeds, etc.

However, thankfully, we’re not yet in an era where you need to become a power user to automate your entire (publishing) workflow. For now, it’s still enough to understand what’s happening, how it works, and what LLMs can or cannot do.

For now, it’s still enough to do what you’re doing best, which is to write in the way only you can write. For some, that may include research tools (Perplexity and NotebookLM), but the end product still comes from your hands on the keyboard, through genuine work and countless hours poured over a single piece of writing.

Have your own questions? Send them. I’ll try my best to answer as holistically as possible!

###

~Z.

This was part 2 of 3 in the Q&A mini series with Andra Watkins. Read Part 1:

China Already Won (And We’re Now Realizing How Badly We Lost)

This is the first of three in a mini Q&A series with NYT bestselling author Andra Watkins. She sent the questions, and I’ll give you my best answers with evidence and systems connections.

Coming Soon: Part 3

Thanks for this very detailed answer, Michael. I still see AI as The Terminator. I use it to streamline research, but I don't actively seek it out for anything else. (I know it is embedded in a lot of life and I use it more than I realize.) I'm also prone to periodically throw something random and weird into my music or reading choices (for instance) because I get tired of AI recommending streams of the same thing. A couple of my books were stolen to train AI, so I'm always diligent about turning it off here on Substack (though that doesn't stop anyone from using my work without my permission.)

I guess I wanted AI to be like The Jetsons. (You may not know that US cartoon.) I wanted it to clean my toilet and similar tasks I hate doing, thus freeing up my time to do what I enjoy. And Instead, I religiously buy dumb appliances because I don't want what comes with smart anything.

A rather long winded article. The attached video was too long for my attention span; I completed about 65%...Regardless of preferences, AI is here. At my home we are working with our Legislature to implement laws to ensure any AI generated text, voice overs, and videos are clearly marked as AI generated with the addition that all citizens have copyright of their own likeness, voice and text materials...